How pupils learn: Rosenshine & cognitive science in the classroom. Questioning, modelling & more

Teaching & Learning at its best

When I started my summer training, I learned about the science of learning, and I quickly realised that teaching is indeed a science. Observing pedagogical research (research into how people learn) can provide teachers with effective strategies to enhance their practice and improve pupil outcomes. Throughout my summer training, I learned about the work of the late American professor, Barak Rosenshine. Rosenshine's 10 Principles of Instruction were originally published in the 2010 International Academy of Education journal and have become increasingly influential in educational research and practice. The research studied cognitive science (the study of the mind) and observed how the brain acquires and uses new information.

As part of the research, expert teachers were observed, and pupil progress was measured through attainment tests. The observations focused on how teachers presented new information, made links to prior learning, assessed understanding, provided opportunities for practice and used scaffolds (specific temporary support for pupils).

After a summer of studying Rosenshine, I was thrilled that my school was a 'Rosenshine school'. Teachers discussed the principles during planning and explicitly followed them when teaching. Staff were also given a copy of Tom Sherrington's book, Rosenshine’s Principles in Action (2019), which I highly recommend.

Tom is a former headteacher who worked in schools across the UK and in Asia. His perfectly sized book beautifully explores and unpacks the principles, and he divides them into four key areas. These include reviewing the material, sequencing and modelling, stages of practice and questioning. His masterclasses on YouTube are also great resources that will deepen your understanding of the principles.

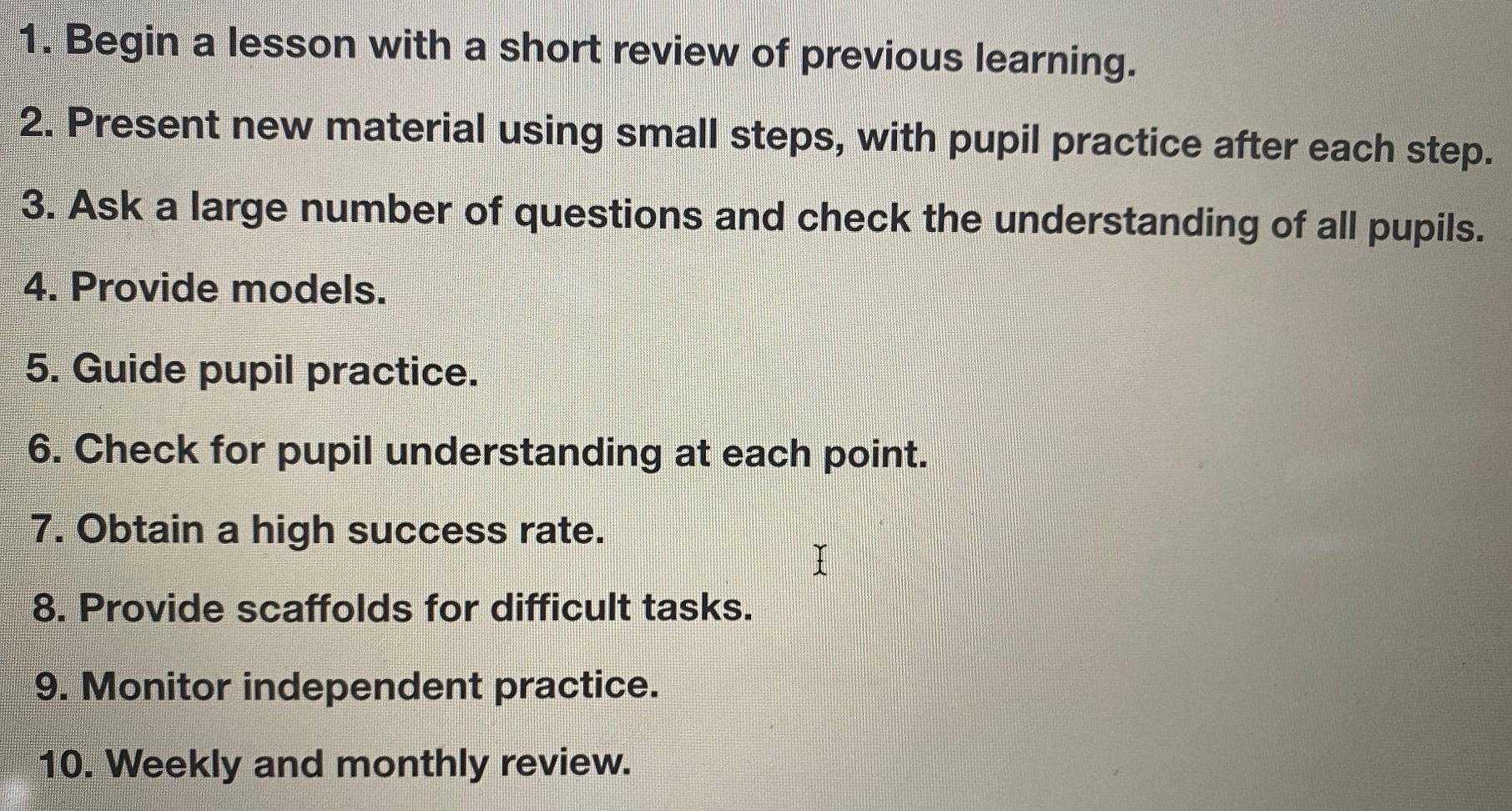

Rosenshine's 10 Principles of Instruction

REVIEW OF LEARNING:

Rosenshine's first principle of Instruction is to begin each lesson with a short review of previous learning. It's an assessment of pupil knowledge and checks back over prior learning. Prior learning and knowledge will feed into the learning that pupils are about to do. Short reviews at the start of a lesson allow teachers to identify pupils who are secure in their learning and those who might need some additional support. They enable teachers to recognise if they need to re-teach parts of a previous lesson and whether the whole class or just a few pupils are struggling with a particular question or topic. A responsive teacher will adapt their lessons to suit the needs of their pupils, to ensure that they're able to meet the learning objective.

Working Memory & Long-Term Memory

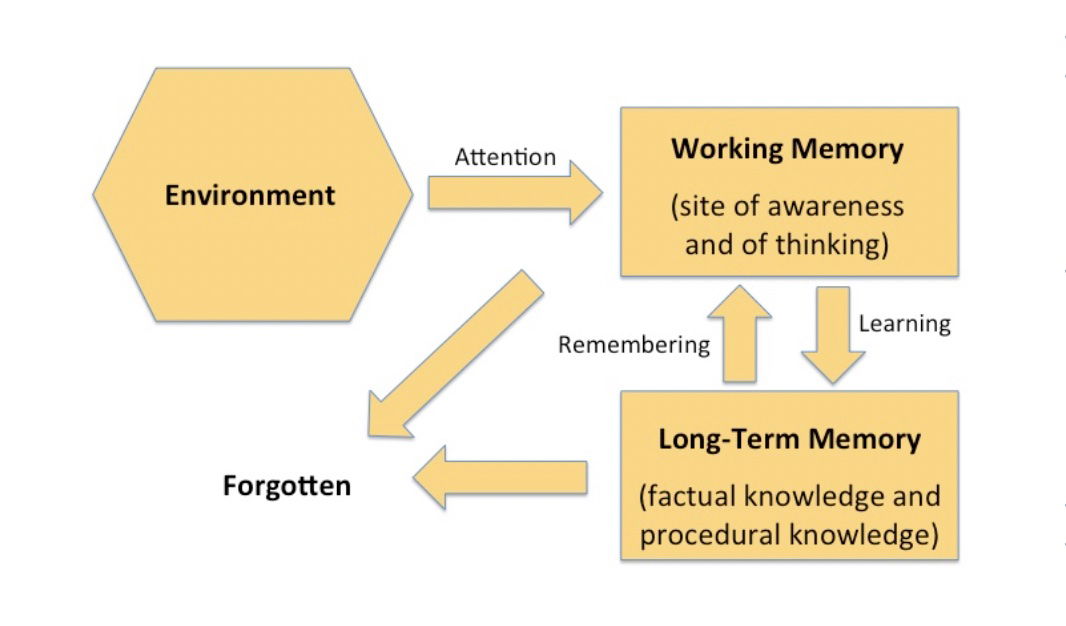

In scientific terms, reviews allow teachers to assess whether pupils have successfully transferred information from their working memory (WM), which is a temporary store with limited storage capacity, to their long-term memory (LTM), which has a limitless capacity.

Learning is a change in the LTM, but the information stored there can be forgotten if it's not retrieved regularly. Willingham's Simple Model of Memory can help us understand this process. When we take in information from our environment, it initially enters our WM. The WM draws on existing information in the LTM to make sense of new aspects of learning. Information in the WM is then either transferred to our LTM or it's forgotten.

Willingham's Simple Model of Memory (2009)

Knowledge builds on knowledge, which is why the WM draws on information in the LTM when learning something new. If previous learning isn't in the LTM, then pupils won't be able to process the following sequential piece of learning. Essentially, they won't be equipped with the necessary information to fully engage in a lesson. Questioning is a key component during reviews, which I'll talk about later.

Rosenshine's 10th principle instructs teachers to do weekly and monthly reviews, to prevent pupils from forgetting information. Weekly quizzes or short monthly tests are examples of retrieval practice, where pupils are forced to remember information and retrieve it from their LTM.

Schema Theory

The Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget suggested that learners construct their own understanding of knowledge by connecting new learning with prior learning and familiar experiences. His schema theory suggests that the assimilation of new knowledge is built on existing schema, which are existing knowledge structures in the brain. The theory suggests that when learners gather new information, they accommodate it in their brains alongside existing knowledge, or schema. Schemas are constantly growing as knowledge is acquired.

Teachers must remember that a child's background, home life and interests can all affect the schemas they have. Pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds might not have developed the same schemas as other pupils, but that's not a reflection of what they can achieve.

Storage Strength & Retrieval Strength

Linking new learning to previous learning is an essential part of teaching. This allows pupils to make links between what they know and what they're currently learning. As they join pieces of information together, they develop their understanding and their schema.

The more a piece of knowledge is connected to memories and other pieces of knowledge, the higher its storage strength and the more likely it is to be remembered. The more we retrieve a piece of information from our LTM, the higher its retrieval strength. If we stop using the information in the LTM, its storage strength will sadly decay, which is another reason why reviews are so important.

Episodic Memories

Teachers want their pupils to remember and retain knowledge, and planning engaging lessons is an effective strategy. Episodic memories involve remembering feelings and experiences, and meaningful lessons that are outdoors, practical, creative and involve the senses can help create these memories. Teachers can transform their classrooms into immersive learning environments and involve interesting resources. Due to their high storage and retrieval strengths, teachers can tap into these memories during future learning.

Stories support storage strength

The use of stories in teaching is a commonly used strategy to support learning. Children love listening to stories, and reading them a book that relates to their topic or creating your own story can be really effective. Stories allow pupils to visualise and imagine, providing further links for learning. These visuals allow pupils to hang their learning on something and can create lasting memories. People really do remember stories, so be a storytelling teacher.

PRESENTING NEW MATERIAL IN SMALL STEPS WITH PUPIL PRACTICE AFTER EACH STEP

You may be wondering why we should present new material in small steps, with pupil practice after each step. Well, being hands-on during learning and 'learning through doing' are huge parts of the learning process. Practice supports the transfer of information from the WM to the LTM and prevents information from being forgotten.

Cognitve Overload

Knowing about cognitive overload will also help you to understand the importance of the second principle. Cognitive overload is the state of having the WM completely filled (Sweller 1988). If a teacher is explaining a complex task with multiple steps all at once, this is a lot for any learner to process. How does anyone expect all that teaching to go into the LTM? Most of it will, unsurprisingly, be forgotten. Coupled with other environmental factors, such as noise, visuals and other distractions, it's very easy for the WM to become overloaded. Cognitive overload inhibits further learning and has a negative impact on pupil behaviour. A pupil experiencing cognitive overload can become frustrated, anxious, fidget or lose focus in a similar way to an overloaded adult learner :).

Small Steps Prevent Cognitive Overload

Breaking a complex new task down into small, manageable steps and presenting new material in small steps creates a systematic way of teaching. It's calm and sequential and produces better outcomes. Pupils are not overwhelmed with information, and their WM's are not overloaded. It's an effective teaching and learning strategy and key to preventing cognitive overload. Pupil practice after each stage of learning also helps to reduce cognitive overload as pupils become more confident and secure at doing something (more on pupil practice below).

ASK QUESTIONS TO GATHER UNDERSTANDING FROM PUPILS:

Questioning is a recurring theme throughout Rosenshine's principles. We don't know what pupils have learned unless we get information back from them, and asking questions is how we assess understanding.

Cold Call

An assessment of learning could involve cold-calling pupils (selecting pupils at random to answer questions). Some teachers use lolly sticks to randomly select pupils to cold call. Each lolly stick has a pupil's name on it, and the teacher randomly selects one from their container before asking a question.

During questioning, no one should feel that they're removed from the questioning circle. My school had a no-hands-up policy, and pupils knew that I could ask anyone a question at any time. This strategy ensured that every pupil was engaged (most of the time) and ready to respond. My school also used the 'No opt out' strategy. If a pupil didn't know the answer to a question, I would ask another pupil and then return to the pupil who didn't know the answer. That pupil was then expected to answer the question correctly, having learned from a more knowledgeable other.

An external trainer once told me that teachers should continue to ask lots of pupils for an answer, even if the first child answers correctly. She went on to say that if the first correct answer is accepted, then all the other pupils immediately stop thinking. It's an interesting questioning technique, as the teacher continuously cold-calls pupils and states that they're not going to reveal the answer just yet. It becomes a bit of a game that children quite enjoy playing. It certainly kept my class engaged.

All Class Response

Getting a simultaneous response from a class, or a whole class response, is another questioning technique that's sometimes referred to as 'show-me'. Pupils could simultaneously hold up their whiteboards to show their responses to a question or use their fingers to show their answers to a multiple-choice question. A short 'Do now' activity at the start of a lesson, such as getting pupils to complete a task on their whiteboards, is another way to assess understanding and review learning.

Process Questions

When questioning, teachers should ask process questions to encourage deeper thinking and to get a thorough assessment of their pupils' understanding. Asking pupils how they worked something out, what something means or why they chose a certain answer forces them to deepen their thinking and explain their answers, methods or reasoning. Teachers should play Devil’s Advocate during questioning to encourage higher-order thinking from their pupils. Bloom's Taxonomy model (1956) shows how teachers can encourage higher-order thinking.

.

.Complete/Full Answers

Pupils might not always provide a full answer to a question and should be encouraged to reframe their answers to provide a complete response. My school expected pupils to answer questions in full sentences and encouraged them to 'say it again better' if they needed to improve their answers. Clarke (2014) states that many answers given by pupils are correct but do not reveal the level of their understanding. She added that the more teachers probe, the more is revealed.

Partner talk or pair-share, is another technique for pupils to deepen their thinking. Teachers should set a question and allocate a time limit for pupils to discuss their answers before reporting back. Mixed-ability pairings allow lower-attaining children to learn from a more knowledgeable other.

PROVIDE MODELS & SCAFFOLDS:

I once heard someone say that if a teacher is not modelling, they're lecturing. Teaching and modelling go hand in hand, and it's a huge part of every lesson. Modelling is simply showing pupils how something should be done or how something should look. Explaining how to do something is one thing, but if a pupil sees their teacher modelling how something is done, it reinforces their learning.

Effective modelling provides direct and explicit instructions that clearly outline the steps needed to achieve something. There's always a set of steps needed to perform a skill or task, such as a tennis serve or simple division, and seeing the steps modelled provides a blueprint for pupils to follow. It makes the abstract concrete and avoids misconceptions. I remember my phase leader telling me to model everything, even something as simple as where pupils should write their names on a worksheet.

Modelling writing for my class

Modelling introduces learning and shows pupils what success looks like. It allows teachers to set standards and expectations, and pupils can be shown the quantity and quality of work that's expected. Modelling allows teachers to set a benchmark for excellence, and modelled work is a helpful resource during lessons.

Modelling helps to avoid any misconceptions and also makes teaching a great deal easier. It clarifies steps and enables pupils to work independently, correctly and efficiently. It ultimately helps to achieve better learning outcomes and better work for your displays :).

Scaffolds

A scaffold is a temporary support (verbal, written or visual) that will enable a pupil to complete a task independently. A scaffold is gradually reduced as pupils become more confident, and it's eventually taken away when it's no longer needed. Tom Sherrington uses the example of stabilisers on a child's bike as a really helpful way to understand scaffolding. The stabilisers are a temporary addition to a bike to enable a child to cycle independently, and they are gradually taken away as the child becomes more confident. One day they're removed altogether as the child is able to cycle unaided. Scaffolds can keep pupils engaged in their learning and reduce the risk of cognitive overload.

A pupil who struggles to innovate stories might have a word mat to support them with their thinking. As the child becomes more confident in generating their own ideas, the scaffold will then be removed. Other scaffolds could involve checklists, cue cards or verbal and visual prompts. Such prompts could direct pupils to the steps they need to complete a task. It's important to note that scaffolds might be in place for longer for children with special educational needs or disabilities, known as SEND.

GUIDE PUPIL PRACTICE & CHECK FOR UNDERSTANDING (GRADUAL RELEASE OF RESPONSIBILITY)

Once pupils have been taught the steps to complete a task, they then need some time to practice what they've learned. Before pupils work independently, guided practice allows for a deeper level of learning to develop and enables teachers to assess understanding. Guided practice builds confidence, and teachers can use it to encourage and praise pupils.

Gradual Release of Responsibility

During guided practice, the teacher is essentially working through a question or task with the class, thinking out loud and asking assessment questions to check for understanding. Asking pupils what the next step is or what should go where allows the teacher to assess the depth of understanding. Guided practice is a collaborative exercise, and pupils follow the same steps that their teacher has modelled for them.

Pearson & Gallagher (1983) described this pedagogy as the gradual release of responsibility, and it's often interpreted as 'I DO' (you watch), 'WE DO' (together) and 'YOU DO' (I watch, I guide or you do it alone). The 'I DO' is the modelling, the 'WE DO' is guided practice and the 'YOU DO' is independent practice. The gradual release of responsibility keeps pupils focused and engaged and builds their self-efficacy.

MONITOR INDEPENDENT PRACTICE & OBTAIN A HIGH SUCCESS RATE

The focus of independent practice is for pupils to demonstrate their level of understanding. It's important for teachers to monitor pupil progress during this phase so that they can spot any misconceptions. Circulating the tables during independent practice allowed me to assess pupil progress and understanding. I was taught to stop the class if two children were struggling with the same thing and to discuss it with the whole class. In some situations, I would bring the class back to the carpet and remodel something to support their learning. Asking another pupil to tell me what I needed to remember for question 2, for example, was another questioning strategy that I would use to aid understanding.

During independent practice the teacher is still a guide, supporting pupils who need it. The aim of any lesson is to achieve a high success rate and for children to meet the learning criteria. Rosenshine's principles enable teachers to create well-planned and well-structured lessons that will transform the teaching and learning in their classrooms.